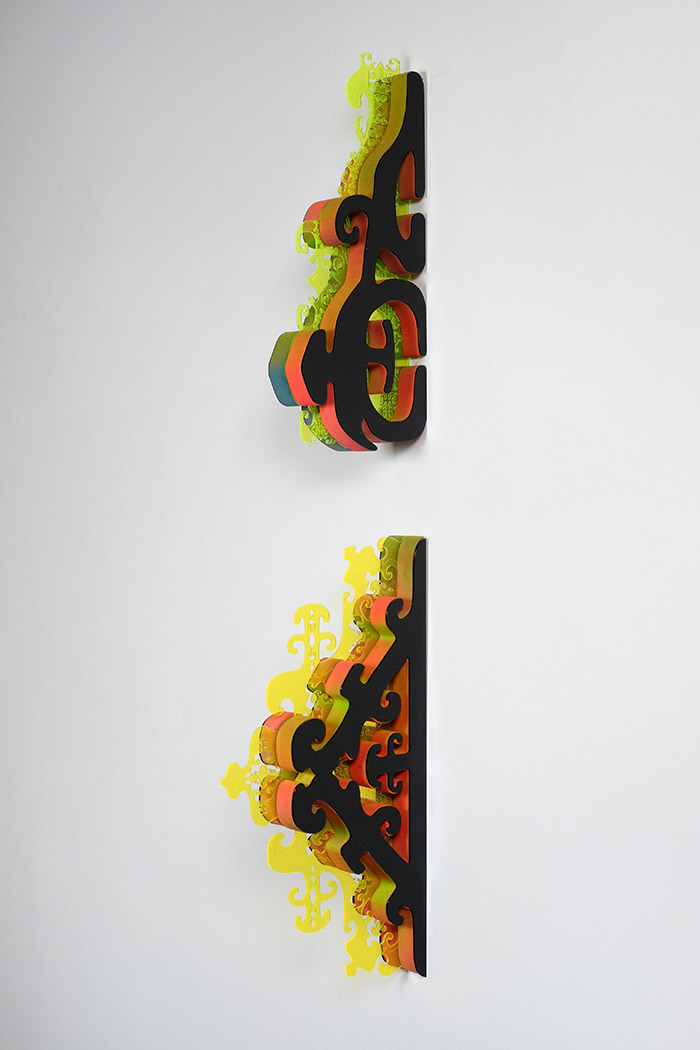

WITCHCRAFT, INITIAL Gallery, Vancouver BC 2015

Laura Brothers, Sara Ludy, Brenna Murphy and Krist Wood, opening Performance by MSHR

Curated by Nicolas Sassoon, exhibition essay by Nicolas Sassoon (published on Rhizome)

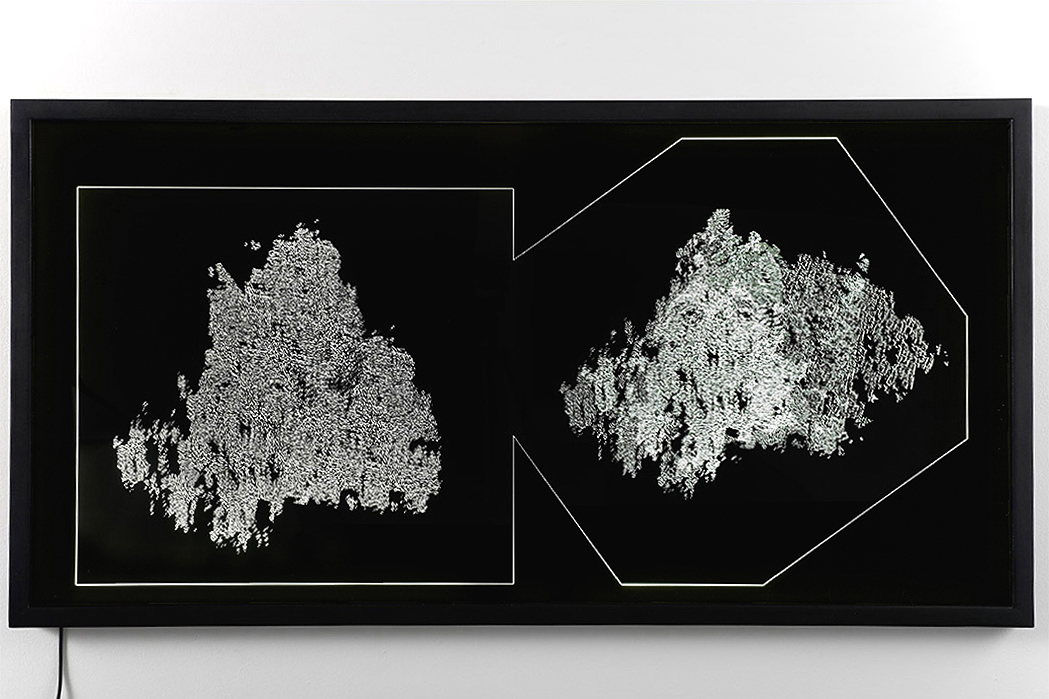

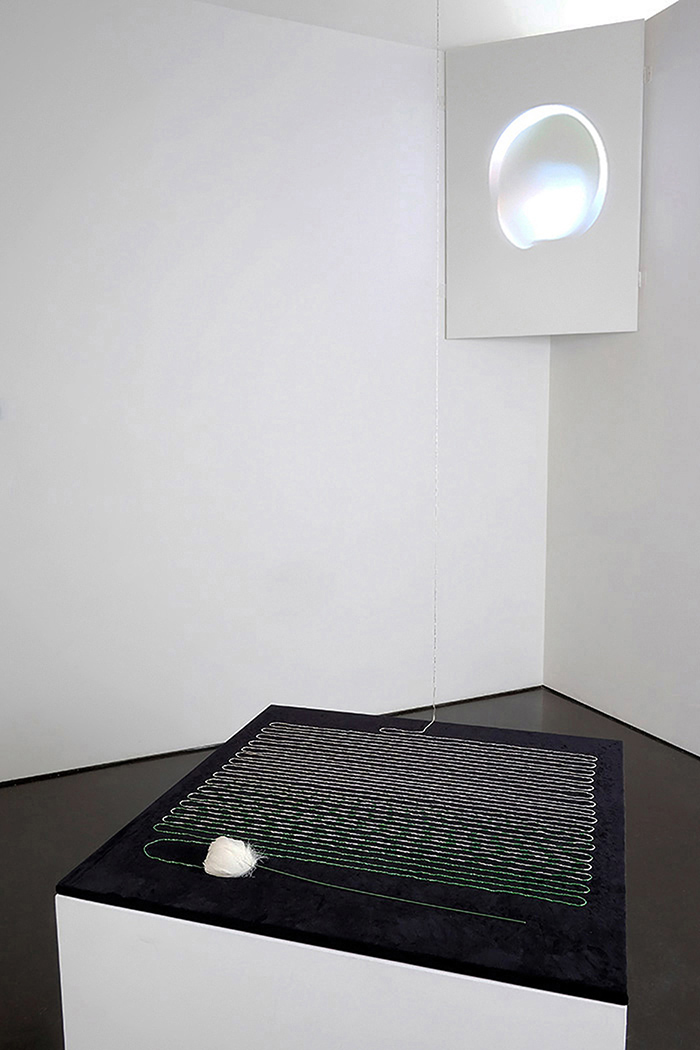

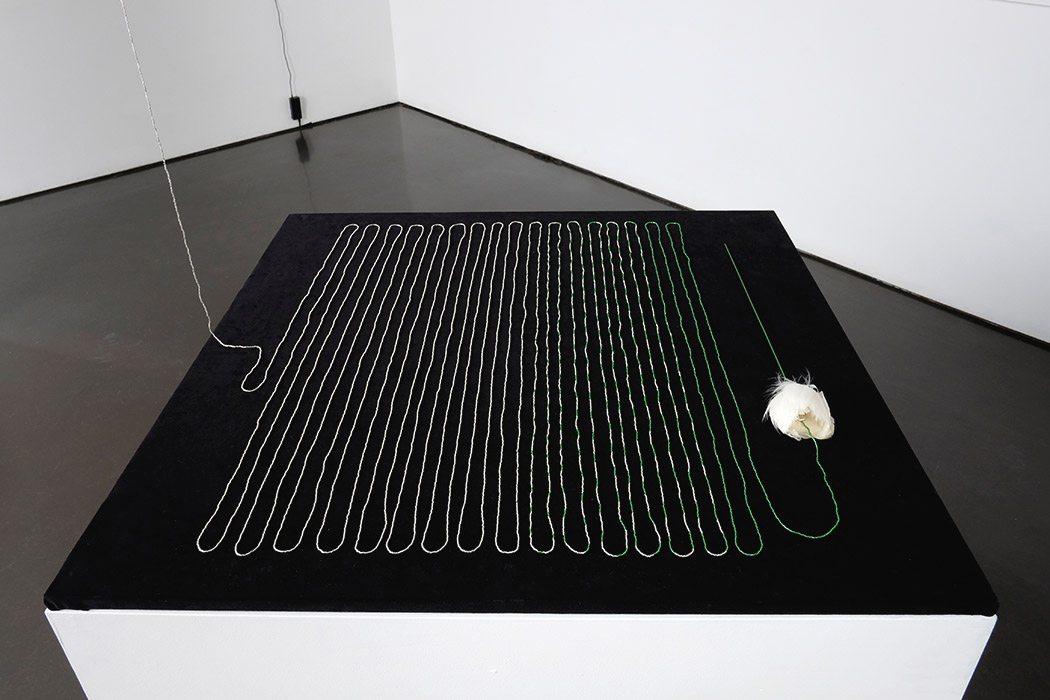

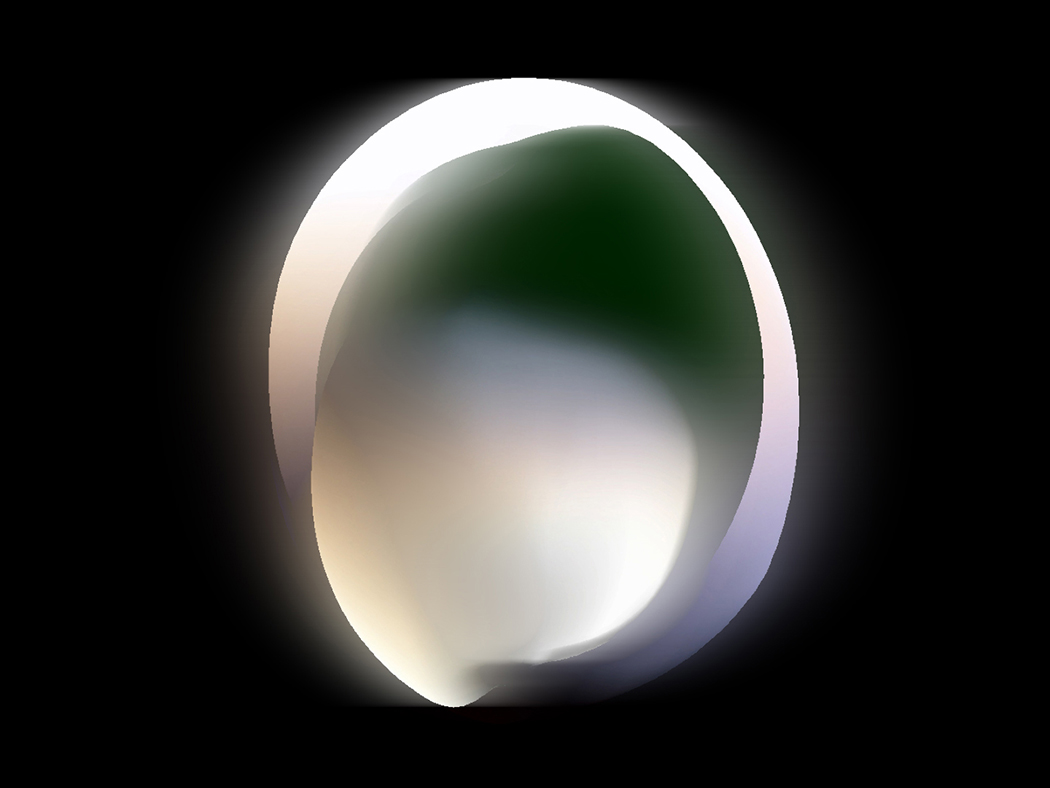

Witchcraft:Craftsmanship, personal mythologies and spiritual queries in the digital realm This essay was written in conjunction with the exhibition WITCHCRAFT, opening February 19th, 2015 at Initial Gallery in Vancouver. WITCHCRAFT features the work of Laura Brothers, Brenna Murphy, Krist Wood, and Sara Ludy. The show, along with the essay, brings a personal reading of the work from these artists; introducing notions of personal mythologies, craftsmanship and spiritual queries as entry points to the reading of these artists’ practices. Within a contemporary artistic landscape focused on self-branding strategies and readability, these four artists appear as valuable voices bringing a poetic breadth to what it means to artistically engage with computer technology and Internet. WITCHCRAFT, as an essay, intends to highlight this aspect as well as the distinctiveness of these artists' work within a historical and technological context and through the lens of my personal experience. “Computing has always been personal. By this I mean that if you weren’t intensely involved in it, sometimes with every fiber in your mind at which, you weren’t doing computers, you were just a user.” Ted Nelson, Computer Lib, 1974. When I joined Computers Club at the end of 2008, my awareness of net-based practices was nonexistent. I had just moved to Vancouver from France and finished creating my first blog as a distraction from solitude. My involvement with online communities was limited to searching forums to modify the HTML of my blog posts. Still, earlier in 2008, I came across the work of Laura Brothers. After browsing Laura’s website extensively, I started a conversation with her via emails and animated GIFs. This conversation led to my involvement in Computers Club, along with the discovery of many artists active within and around that platform at the time. In 2008, Computers Club was a unique collection of internet personas, particularly committed to shaping the intricacies of their online space. Many of these artists displayed an endless accumulation of content scattered across multiple websites, while revealing little to none about their identity. The collective’s website acted as a gateway to access most of the content (along with other websites), a “central station”—mysterious about its inner workings—where the navigation would begin. The accumulation of works from each artist delineated the backgrounds of enigmatic characters, modeling personal mythologies through visual vernaculars and experimentations. Between 2008 and 2011, I encountered through this platform the work of Laura Brothers, Sara Ludy, Krist Wood, and Brenna Murphy. Their collection of online works was constantly updated, bringing weekly developments to their digital territories and at the same time increasing the frequency of my visits. Creating and publishing artworks online and making work in a studio are quite different things. Today we say post-studio practice, aiming to encompass some aspects of these changes, although this term mainly highlights a technologically engaged practice becoming readable to an art audience. However the four artists mentioned above seem to have developed a different kind of practice early on, a practice not necessarily geared toward legibility. While displaying a clear knowledge of the tools they are using, their production can remain hard to decipher and are seemingly determined by unclear factors. A couple of factors appear communal however: the first is the belief in publishing immaterial works online as a significant and complete gesture. The other may have more to do with a singular application of computer technology in one’s life: How does an artist naturally engaging with digital tools develop an immaterial practice outside of artistic conventions? How do these spontaneous uses of technology bring singular developments in art? After browsing Krist Wood’s website following my introduction to his work, my understanding of the implications behind making a personal website became very different. Wood is one of the founders of Computers Club (a few years ago, in an artist profile for Rhizome, he gave a minimal definition of the online collective—“a set of identities that derive from computer users”). His website is a good example of this definition; it offers an almost purely visual environment where navigation and meaning are certainly not given. Each work remains mysterious about its genesis. Projects like Mausoleum I and Mausoleum II invite to explore natural settings outwardly frozen in a dream-like state. The viewer has to find their way through each image to access the next, encountering architectural structures where the difficulties of navigation seem to expand, to finally uncover spectral digital relics. Proceeding through this web space is often akin to hovering amidst the ethereal structures of an individual’s mind. It demands time and effort to comprehend the navigation, but the experience and the results are always fulfilling. Through Wood’s work, my understanding of a personal website went from the making of an optimized “easy-browsing” promotional platform to the construction of an uncompromising extension of online self; the creation of a personal mythology in all its complexities, to develop particular facets of individuality in their most elaborate convolutions. As an artist, composer, computer user and scientist, Krist Wood’s online presence is also significant for its circumstances of existence; created amidst a scientific career, maintaining a relative form of anonymity and resisting academic legibility. These conditions appear quite relevant of the distinctive paths artists can now take to develop creative practices outside the norms via Internet and digital media. While an unexpected route can be necessary to consider when creating an identity online, it remains incomplete without bearing in mind the technical challenges of contemporary digital image making. The vast majority of computer imaging tools available today have become ubiquitous—everyone is given (almost) the same rake and sandbox to play with—and in numerous scenarios, professionals are taking on delicate tasks at the service of artists. On the individual scale, many productions made with these programs end up very similar and transient, because while being omnipresent the tools are also complex to master and ever changing. They come with their own paradigms and standards of production; everyone will get to experience the joys of the Photoshop lens flare and similar software trends. Given this context it seems fair to wonder what’s left for artists who want to develop a unique and thorough voice without hiring a Hollywood CG crew. When I first came across Laura Brothers’ live journal, I didn’t think her work was the answer to this complex inquiry, but it was definitely an answer to my private interrogations around this matter. Brothers’ work answers a complex question—context—with a simple answer: context. Her work is created on a computer screen, and therefore develops visual characteristics inherent to computer screens. Most of the work is activated through the act of scrolling, revealing optical qualities through motion with an endless satisfaction. Her drawings emulate early computer graphics far beyond their historical connotations, employing them to form a visual terminology of shapes repeated through series. Within each series we observe figures, eyes, gloves, and obscure shapes organized through an acute sense of composition and abstraction, and through the repetition each element slowly consolidates a cohesive menagerie of signs. Brothers’ work is a sequence of visual experimentations enabling the development of a strong artistic identity. Browsing the blog archives brings the satisfaction of recounting one research leading to the next through the force of accumulation. Producing such a singular body of work through digital tools requires commitment; it is an ability that slowly unfolds itself against the immediacy of current software’s inclinations. This level of commitment to a digital practice doesn’t always develop through such an exclusive path; it also grows through other methods. When Sara Ludy worked as an interior designer and resident VJ in Los Angeles, she was nurturing several personal projects that were nonetheless informed by both of her jobs. The knowledge acquired in each field became essential to Ludy’s art practice to relocate professional skills within the context of her own objectives—an ambition for the design of human space and a unique approach toward the incorporeal properties behind domestic architectures and objects. This resolve started through the production of uncanny environments extending professional assignments: frescos of otherworldly interiors employing digital collage techniques from interior design, videos depicting the human body within complex geometric structures as developments from VJ experiments. Shortly after, a multitude of projects took form, bringing a closer scrutiny to the aura of real and virtual spaces through photography and found imagery. In the meantime, Ludy began to dig deeper into the spiritual significances of architectures and artifacts from various cultures through online research and visiting historical sites. This research led to recent projects like Dream House, where Ludy renders the oneiric architecture of a lucid dream, stepping outside the screen to offer supernatural reflections on the making of domestic and virtual space. The last iteration of this approach resides in her project “Rose”, where Ludy employs laborious craft and 3D modeling to project the aura of a mass-produced object, suggesting a poetic relationship of preservation and footing between a digital and physical body. “For me, graphics programs are spiritual tools that allow one to psychedelically engage with the fabric of reality. I'm deeply committed to pushing the innovative possibilities inherent in these contemporary folk art tools.” This statement by Brenna Murphy defines her practice from the start as a spiritual enterprise. Part of Murphy’s work begins with simple hand-drawn forms which manifest on her computer screen as vector and extruded shapes. The shapes are then given digital textures, the number and diversity of shapes increases exponentially to rapidly form endless maze-like structures. The scale of this meditative repetition within her work becomes perceptible when browsing her website, displaying gigantic HTML pages offering countless perspectives on the results of her procedures. One striking element within Brenna Murphy’s work—aside from its beauty—is its scale and depth, seemingly infinite and continuously recalibrated as it keeps expanding online and in space. But another striking element of her work is her spontaneous engagement with computer technology to develop a personal approach of mystic traditions and spiritual notions. The aptitude to initiate such a journey through computer technology brings to mind an essential aspect of digital tools: their ethereal field of existence in which they allow us to engage. Of course it would be naïve to think that Internet and digital tools are not falling under physical contingencies; computers are built by humans, they consume power and they pollute significantly. But it would be equally naïve to ignore that internet and digital tools can be used toward the most personal, spiritual, and creative expressions of one’s self. When net-based practices are contemplated for their branding strategies, corporate aesthetics and optimized readability, the artists discussed here seem to require another evaluation, as they embody striking examples of uncompromising creativity online far away from these criteria. Their practice belongs to another essential field of Art online—determined by idiosyncratic and poetic initiatives focusing on timeless questions of personal mythology and spirituality. This Art online provides a refreshing inspiration and resistance against the intense rationalizing of computer technology; engaging with the digital should also happen through mystical ways. Nonetheless, the level of dedication of these artists commends another observation; it is their ability to avoid the pervasive shortcuts of computer technology that constitutes a foundation to their art. At last, this particular field of Art also responds to a personal interrogation at the origin of my involvement online; how can the Information Age still provide a space for dreaming? |